Italic lettering, and how to form italic letters

Originally developed for use by clerks and secretaries in the Pope’s office, italic lettering now lends itself to many more worldly purposes.

Because it is elegant and legible, italic is most appropriate for writing out longer calligraphic texts such as sonnets, passages of prose, wedding invitations etc.

Italic calligraphy is a little more decorative than roundhand, but maintains a very regular appearance. This is partly to do with the letter-forms themselves and partly about factors such as spacing and proportions.

So, anytime you want people to be able to read easily what you have written, and at the same time for them to notice that the writing is beautiful and a little formal, consider using italics.

Italic lettering step-by-step

If you haven't already seen it, you might be interested in the 'italic calligraphy' page, which gives some general practical tips on how to write the script.

This page now goes into the nitty-gritty of exactly how you form italic lettering. There are several basic movements which you will use again and again for similarly shaped letters. Learn these and not only will your italics improve, your everyday handwriting may well benefit too.

So, have you got your calligraphy pen and practice paper ready? Five nibwidths measured and ruled? Let's start.

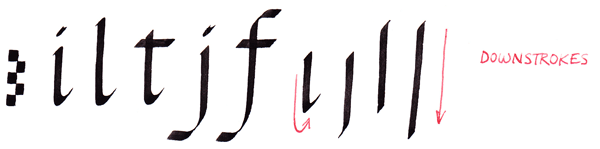

You may already have seen the illustration of an italic letter 'a' on the 'Italic Calligraphy' page. (You'll see it again further down this page.) However, we're not going to begin with 'a'. Instead, we're going to get straight into the fundamental structure of an italic alphabet: the downstroke.

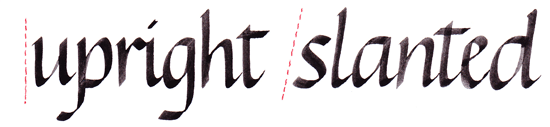

Notice that your downstrokes should all be parallel. For different letters, they begin and end in different places above, on or below the baseline. But each time the stroke is slightly slanted off the vertical, and is also parallel with every other downstroke.

The downstrokes above are not very slanted. They could be more so.

Note here too that there are different acceptable ways to start and end a downstroke. Sometimes they begin with a little 'tick' from the left, sometimes with a thin slant from the right. The main thing is to use a tiny motion of the nib one way or the other to get the ink flow cleanly started for a well-formed letter.

Don't mix methods within the same passage of italic calligraphy!

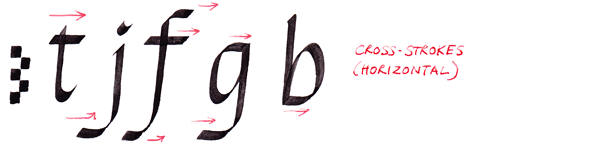

Of course it is just 'i' and 'l' that are formed of only a downstroke. Other letters need a horizontal line or cross-stroke to complete them, so practise drawing smooth horizontals too:

Don't worry about 'g' and 'b' for the moment. They come up later on with their complicatd curves. I just wanted to show you that horizontals are important for several letters. The italic forms to practise right now include just 't', 'j' and 'f'.

Notice that the 'tails' on descenders, for 'j', 'f', etc, are formed by joining a cross-stroke to a downstroke with a slight curve into a thin line. Although the strokes are almost at right angles to each other, they do not join by forming a sharp corner.

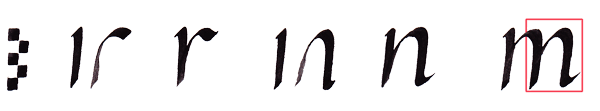

Once you can draw a short downstroke and a horizontal, it's time to combine them in a different way again by using a branching stroke. This 'branch' is a key element in italic lettering.

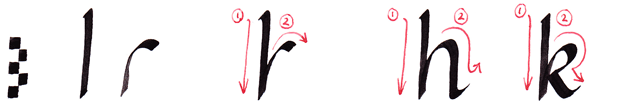

Here it is in its simplest form to write an italic letter 'r':

Notice how the same branching stroke forms the 'r' when stopped high, but if carried on down forms an 'n'. Equally, a slightly narrow italic letter 'n' without a final flick is the first half of an italic 'm'. See how in the final 'm' there are two 'n's joined together? (I've drawn a red box around the second one.) Italic lettering is very much about repeated shapes.

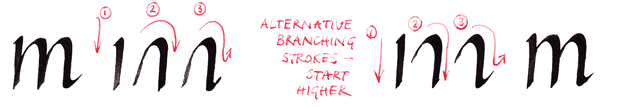

In the illustration above, I have shown the branch drawn right from the bottom of the letter at the baseline up 'through' the first downstroke. This method gives a more cursive feel to the letter and will help you to write italics more rapidly and fluently in time.

To push the nib up you must hold it very lightly, keeping it always at 45 degrees, and 'skim' it gently up across the page into the branching point. As the pen stroke begins to curve diagonally up to the right, separating from the downstroke, you can let the nib 'bite' the page a little more. Once you are into the next downstroke, put normal pressure back on the nib.

So the rule is pressure right off for upstrokes, light pressure on for downstrokes.

However, if you find it difficult to do upstrokes at all, you can start your branching higher up, as follows:

The first 'm' is drawn with the more cursive upstrokes. The second is drawn with diagonal strokes starting higher. Try to make sure your arches are smooth with no sharp internal angles where they meet the downstrokes.

Once you have got the hang of drawing branching strokes, a couple of other italic letters come within reach:

The italic letter 'h' as you can see is an 'n' with a high ascender to start with. Make sure the second, shorter downstroke is parallel with the first.

The 'k' should start its branch just like an 'n' or 'h', then tuck sharply in to form the bow. Draw the leg out so its foot strikes the baseline a little back from the furthest point of the bow. This helps gives the body of the 'k' a slight slant, in line with its ascender and the rest of the italic alphabet.

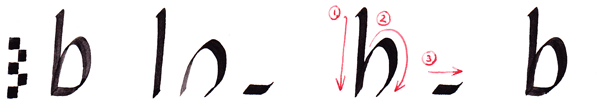

Two more letters formed using the italic 'branch' are 'b' and 'p'. They are just the same except that one has an ascender, the other a descender. Here is 'b' to start with:

When drawing an italic letter 'b', form the branching curve quite narrow at the top and let it bulge out a little, gracefully, before curving back in again towards the base.

The horizontal joining stroke should not be too long and square or your 'b' will look clunky.

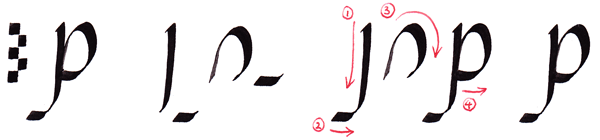

Here is 'p', for which exactly the same rules apply:

Okay, I realize that I didn't mention that little 'tail' on the downstroke of the 'p'. It makes it fit with 'g', 'j' and so forth.

(For a flourish on ascenders in italic lettering, you can draw a horizontal off the top of the letter towards the right, just like the tail on the 'p' in reverse. Then the 'b' would be an exact duplicate-in-reverse of the 'p'.)

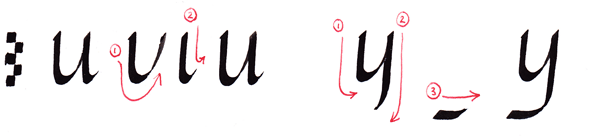

Now for a different kind of branching stroke:

These two italic letters look quite simple to draw but make sure your pen is at 45 degrees and that you have a slight slant on your downstrokes so that you get a good contrast between the thick and thin.

Again, the version I show uses an upstroke. If you have trouble with that, stop the curve of the letter-form before it starts moving upwards, and draw your downstroke to join with it.

Branching strokes should be practised a lot. Now is a good time to learn about arcades. These are exercises consisting of rows and rows (and pages and pages) of scallop-shapes like multiple 'n's and 'u's:

It is also very useful to find sequences of italic letters like 'minimum', 'nilulinul' or 'munumini' and to write these repeatedly to practise transitioning from one form to another within a line of italic lettering.

(This is also excellent cursive handwriting practice, by the way.)

Enough munumini? Enough branching strokes? Never fear, you will be back to practise them some more before long :-)

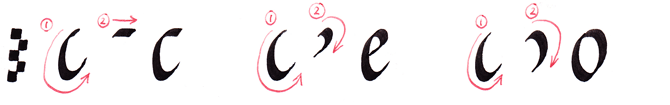

Let's get onto some curved letters:

Notice with these three that the same basic movement is used to create the first curved stroke.

Remember that italic lettering has a slight slant, so the bottom curve of these letters should be positioned a little further to the left than the top curve. That is decided when you make the first stroke. Draw it to fit an imaginary slanting line.

After drawing that first curve, 'c' has a short, quite straight top.

By contrast, 'e' loops round very tightly with a longer hairline diagonal to meet the downstroke.

Make sure your 'o' is not circular but oval, and also slightly slanted. Imagine it is made of two tiny circles, one on top of the other and offset to the right. Draw round these two tiny circles and you'll get the slanting oval 'o'.

Drawing line after line of 'o's is another valuable exercise. I won't illustrate it here. You can imagine all those zeros easily enough. (Draw a '1' at the beginning and visualise the page as next year's income ... )

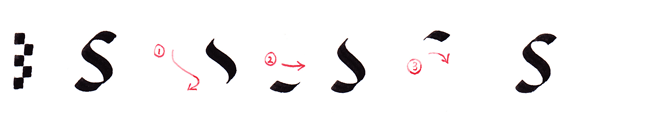

Now for another rounded letter made of two offset circles:

This is another letter which it pays to practise again and again. (Maybe I have said that for all the italic lettering so far. It's true.)

There are two main pitfalls with 's' as an italic letter. One is to make the finishing-strokes too horizontal and straight. This makes the 's' look spiky. Another danger is to make the first snaky wiggle too wide and horizontal. This leads to an 's' with no slant to it -- a roundhand 's' instead of an italic.

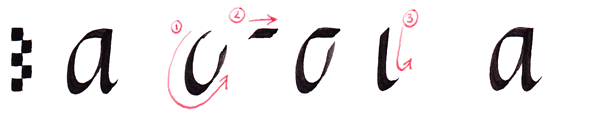

When you are reasonably happy with 's', it's a good time to move on to a whole new family of italic lettering forms:

To form an italic letter 'a' you may push the pen back a little from right to left to start with. Bring it round in a smooth lozenge shape, with a slightly pointy base somewhat over to the left. (This is what gives the body of the letter its slant.) Add a cross-stroke at the top and a crisp downstroke at the same slant as the rest of the letter (and any other italic lettering on the page).

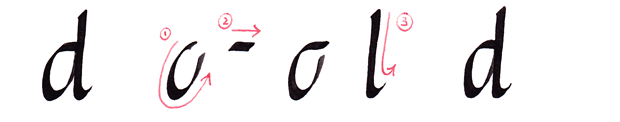

The same technique applies to 'd', with a long descender instead of a short downstroke:

Try to get the descender of 'd' to overlap the upstroke perfectly. The bottom half of the letter should look just like an 'a'.

(The 'd' looks a bit smaller than the 'a' here, but it's just the way I saved the graphics. It's still 5 nibwidths high.)

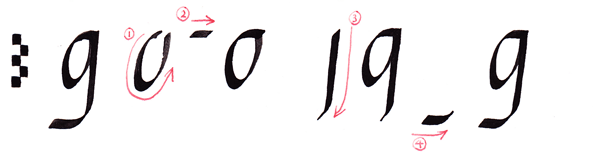

Same again, with a descender this time and a tail, for 'g':

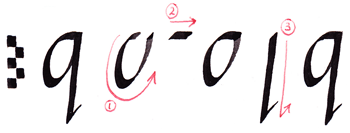

And as you can imagine, it's if anything even simpler to draw a 'q' in italic lettering:

That takes care of quite a few letters.

Try to make sure that 'a', 'd', 'g' and 'q' in your italic lettering have the same basic body-shape as each other.

Also, you should notice that the curve of the first stroke in these letters also closely resembles that of 'c', 'e' and 'o'.

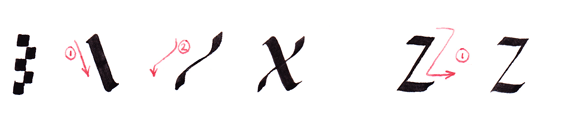

There are four letters left. I think of them as 'the pointy letters' but it is probably better to call them 'diagonal' letters as they are composed mostly of straight diagonal lines. Let's start with two that closely resemble each other:

Don't go overboard with the curve on the last stroke. It's pronounced but shouldn't be bulgy.

Also, make sure that you draw your downstrokes on 'v' and 'w' closer to the vertical than the thin upstrokes. By contrast, the upstrokes should be more angled across to the right. This again is about getting a slant onto all of your italic lettering.

Last two letters!

This form of 'x' is really quite gratifying to draw. It is elegantly easy to form but looks fabulous with its little 'ears'.

As with 'v' and 'w', make sure that the first, thick downstroke of 'x' is closer to the vertical, and the thin cross-stroke is more slanted at an angle. Otherwise, if both lines are at the same angle, the 'x' will look too upright compared with the other, slanted forms in your italic lettering.

By contrast with 'x', 'z' in italic is rather plain and surprisingly difficult to slant properly. Practise makes perfect ...

I think and hope we have now covered the alphabet.

Capital letters in italics is a whole other subject. I hope you will soon have a chance to practise those from another page on this site.

One of my long-time visitors and a calligrapher now in her own right, Silvia, has pointed me to a series of instructional videos by the great Lloyd Reynolds on italic writing, which you may find helpful! Thank you, Silvia.

Meanwhile I trust you will have fun with the italic lettering skills you have learned here! Why not compose a sonnet as a gift for a friend, and then write it out in elegant italic letters?

And of course, if you've got this far and would like to see something particular about calligraphy on this site, drop me a line via the

contact form and I'll be delighted to do my best. (And your email address will be kept strictly private.)

Go to 'Calligraphy Alphabets' overview

Go to 'How To Write A Sonnet'

Return from 'Italic Lettering' to Calligraphy Skills homepage